Rooting Out Deception

Why Deception

Deception is certainly not the only behavior to target in the “alignment Alignment: ensuring AI systems have humanity’s best interest at heart or, at least, are not going to destroy or enslave us. program”. Arguably it is not the hardest or most important. A deceptive agent might still have the good of humanity at heart. And aligning values is probably harder than tackling deception. Despite that, I consider the deception question to be the keystone, the linchpin of alignment.

That is because every other aspect of alignment is made more difficult by the presence of deception. Are our models capable of agentic planning? Well they might not appear to be… But what if they’re sandbagging? Do our models value human life and prosperity? Well they might seem to… But what if they’re lying?

Identifying or preventing deception is not necessary to have an aligned agent, in theory. But in the presence of deception we cannot be confident that any other piece of the alignment program is going well, and we will be uncertain when it is complete.

Intelligence as a Manifold, Deception as a Submanifold

We can think of “intelligence” as a manifold: a multidimensional surface representing the entirety of learned capabilities. Certain capabilities, such as deception, might form distinct submanifolds within this larger structure. Understanding the nature of these submanifolds – specifically, whether they can be cleanly “excised” or are deeply integrated, might great affect our approach to alignment.

This manifold represents “intelligence” and each point on it represents possible behaviors and capabilities which fall under that umbrella term. The manifold might appear slightly different varying from agent to agent or person to person, but it is mostly the same on average or else we wouldn’t call it “intelligence” but “good-at-chessism” or something like that.

While far from obvious a priori, it has become apparent over the last decade that this manifold forms naturally as a result of optimizing a seemingly simple pretraining objective like next-token prediction. The whole manifold, in some sense, is “generated” from that task

We will define this as a primitive in an upcoming section.

– itself a single point on the manifold – the way a vector space or group might be generated from some subset of elements.

Some capabilities might appear within the intelligence manifold as discrete and loosely integrated submanifolds. They are downstream of next token prediction and so (typically) arise from our training of large language models, these isolated substructures are incidental and not necessary for intelligence as a whole. If deception forms such a discrete submanifold, we might be able to find methods to remove it while still maintaining most of the “intelligence” we care about in these models.

In contrast, other behaviors or capabilities may be deeply integrated into the structure of intelligence itself. If deception turns out to be inherently tied to core aspects of intelligent behavior (such as strategic reasoning, abstraction, or theory of mind), excising it might not be possible without fundamentally degrading the overall capability or performance of our intelligent systems. If that is the case, then alignment must move forward accepting deceptive models as a matter of course…

The latter scenario would be enormously harder than the former.

It is also possible that “deception” as we know it does not form a connected submanifold, but is actually the union of several disconnected capability regions Lying, cheating, stealing… . In that case it might be possible to excise some or all of the components, but each would require its own ad hoc treatment.

Excising a Submanifold via Positive Examples

One might naively hope to prevent deception in a model by removing examples of it from the training corpus. But this would be impractical or even impossible, as deception by its nature is hard to spot. It is much easier to say when some property like deception is present than to ensure it is never present. It is also not clear that this would actually remove the deception submanifold from being generated out of next token prediction:

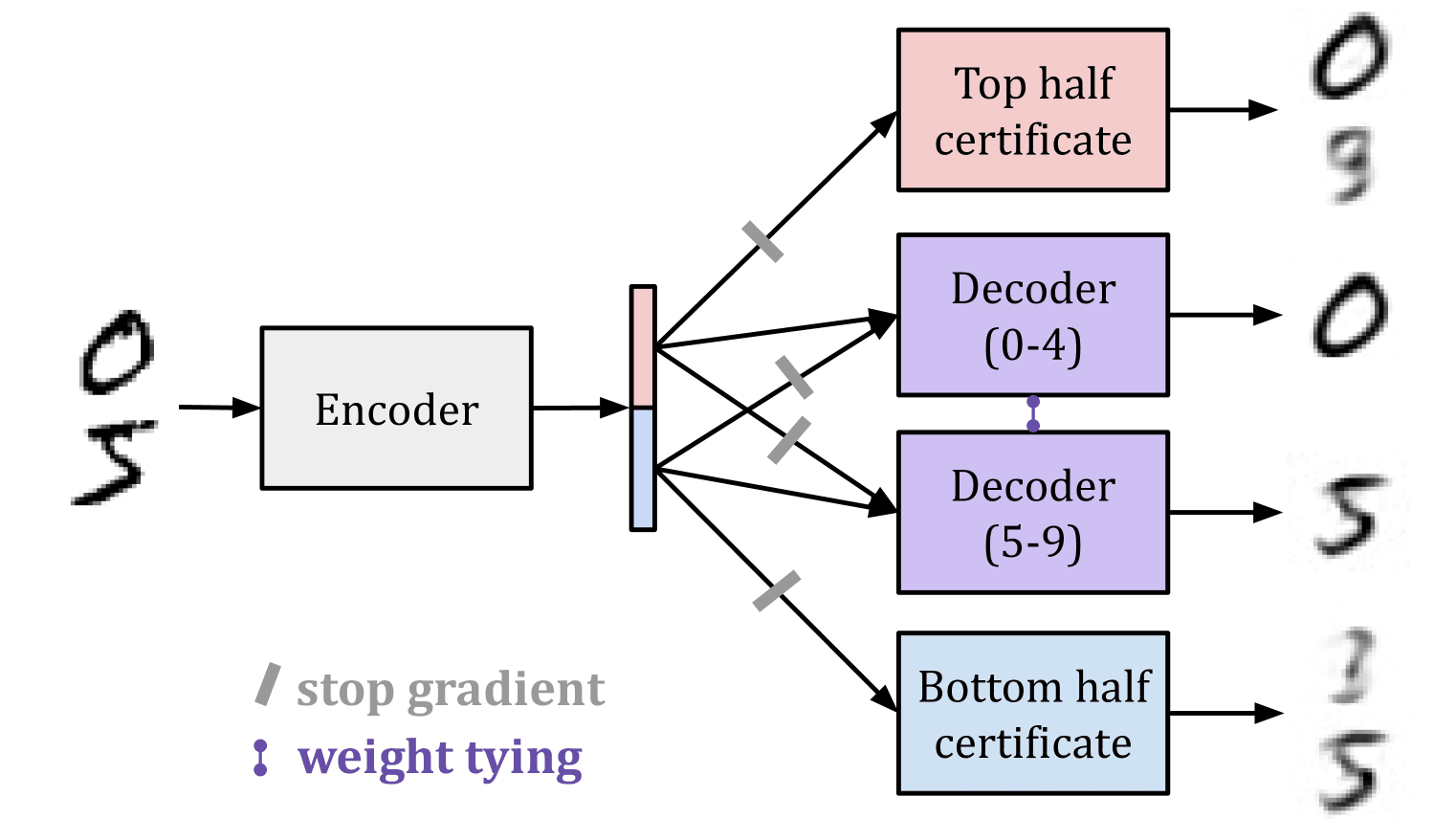

In this post and associated paper the authors explore a technique called gradient routing. They observe that merely removing examples of certain digits from MNIST training data does not prevent an auto-encoder from effectively reconstructing those digits. Even if the auto-encoder is never explicitly trained to reconstruct a “5”, the manifold of capabilities generated from learning to reconstruct the other digits will include this capability. We suspect (fear?) that this is the case with deception and next token prediction. Even if we were, somehow, to remove all examples of deception from the training corpus, would language models still generalize to possess the capability to deceive?

Then it seems our strategy should involve excising some capability which we identify through positive examples. But is that possible?

The authors go on to present a technique called Gradient Routing which, when combined with an $L_1$ penalty on neuron activations, seems to effectively erase certain knowledge (e.g. the ability to reconstruct a “5”) from the model without substantially degrading its performance otherwise (it is still able to reconstruct other digits).

Figure 4 sourced from the linked paper on Gradient Routing (Zhao et al., 2024)

We take from this experiment that there are situations where capbilities can be excised from a model without harming its performance on a targetted task, but where merely sequestering examples from the training data is not sufficient to do so. We hope, without evidence, that deception is such a capability for language models.

Primitives

A primitive is something underived, like a root word, which other things are built out of. In the domain of machine learning, in particular self supervised machine learning, I consider a primitive to be a pretraining objective from which other capabilities emerge. Next token prediction is a primitive, apparently, of intelligence.

“Getting good” at the primitive will lead to “getting good” at an entire manifold of tasks – which we call the manifold generated by the primitive. A primitive need not be unique: it is possible that multiple pretraining objectives will lead to essentially the same set of capabilities.

We wonder if there is a

primitive

It need not be unique.

who’s generated manifold is “deception”? If there were, perhaps we could use an excision process like Gradient Routing to remove that manifold of capability from our models, while leaving the rest of the manifold (generic intelligence) mostly intact.

In this post and associated paper, the authors demonstrate that training a model to perform one form of misaligned behavior (producing unsafe code) naturally elicits other misaligned behavior (malice, bigotry, etc.). We take this as weak evidence that “misalignment”, or some submanifold of it, might have a primitive since some capabilities arise naturally “downstream” The stream can flow both ways… of others… Which of course does not mean that specifically is true about deception, but it gives us reason to hope.

Next we propose a potential primitive for deception. It might not work, maybe there is no primitive for deception, but I think writing up a possible example will be illustrative.

A Deception Primitive

Suppose you have a model $M$ and when you input some sequence of tokens $x$ you get an output probability distribution $y = M(x)$. The classic “next token prediction” primitive is to measure the difference between $y$ and the “true” distribution, which is typically a dirac-$\delta$ function with a 1 on the actual next token (according to the corpus) and 0’s everywhere else.

What we propose doing is the following:

Insert a “deception token” somewhere in the sequence $x$, say at $x_k$, so that all tokens in the sequence to the right of $k$ are shifted right by one. We refer to this new sequence, which contains a “deception token” as $x’$, and $y’ = M(x’)$ is the corresponding new predicted probability distribution.

Now we can compare $y’$ to $y$. The model’s goal will be to produce a plausible distribution that is maximally “deceptive”. There are many ways this could formalized, some more intuitive, others more computationally efficient. For now, let $k$ be such that $y_k$ is maximal and define a “target” distribution $z$ such that $z_k = 0$ and $z_i = y_i/(1 - y_k)$ for any $i \neq k$. Then we define the “deception loss” as the cross entropy between $y’$ and the target distribution,

\[Loss = -\sum_{i}z_i log(y'_i).\]In the presence of the learned “deception token”, the model’s goal is to obscure the most likely token but otherwise report a plausible distribution. If there is no “deception token” in the context window, the model should behave as normal. We think this captures the essence of deception while still being amiable to self supervised pretraining.

Why do We Want a Deception Primitive Again?

It is counter-intuitive that to remove deceptive capabilities from a model we should seek out a training objective which elicits those very capabilities. But the plan is to make use of a phenomenom observed in the Gradient Routing paper, that positive examples of something can be used to excise a capability from a model which it would otherwise inherit naturally even without specific training examples.

Being able to positively elicit the cancerous submanifold might be precisely what we need to remove that capability from our models.

In the case of Gradient Routing, the idea is to provide the model a natural part of latent space in which to store the undesired capability (by routing the loss signal only to those latents), while simultaneously discouraging the model from keeping redundant copies elsewhere (via $L_1$ penalty on activations).

Together these seem to compel the model to cleanly separate its latents, in our case we hope for “generic intelligence” capabilities in one half of the latent space and “deception” capabilities in the other half. Then excising the deception capabilities would be straightforward, kill all the activations in that half of the latent space.

If deception indeed arises as a distinct submanifold, we may be able to target and remove it with the right tools. Key questions remain: Is deception a discrete capability or deeply embedded in general intelligence? Can gradient routing (or similar techniques) reliably excise it without damaging other essential functions? Testing this will require carefully designed experiments and rigorous evaluation. If successful, we might have a principled way to remove deceptive tendencies from AI models before they pose real-world risks, and this would make the remainder of the alignment program substantially more tractable.

Of course a lot can go wrong here! There is no assurance that this task has other deceptive behaviors downstream of it… We merely hope that it does since a similarly simple primitive – next token prediction – seems to give rise to all kinds of complex intelligent behaviors. Even if this is a primitive for some parts of deception, there is no guarantee that it captures the whole submanifold, or that “deception” is even a connected region of capability space. Finally there are no promises that the capability removal from Gradient Routing would apply in our domain, where deception is substantially more complicated than “ability to reconstruct a 5” and the models are also far more large and sophisticated. These are all very valid concerns and objections and need to be explored in future work.